On 25 December, the Banaadir Regional Administration conducted municipal local government elections in Mogadishu, marking a historic institutional milestone after a lapse of fifty-seven (57) years without district-level local elections. The polls represented the first systematic attempt in decades to reconstitute municipal governance through an electoral process grounded in formal administrative structures rather than appointment or ad hoc political arrangements.

This election was significant not merely for its timing, but for its constitutional and administrative implications. It signaled a deliberate transition toward decentralized urban governance, restoring the role of districts as meaningful units of local representation and public accountability. In a city long shaped by conflict, demographic fluidity, and centralized security administration, the resumption of municipal elections reflected an evolving commitment to participatory governance, civic inclusion, and the gradual normalization of local democratic practices.

Against this historical backdrop, the district-level voting data generated by the 25 December elections provides a rare and valuable empirical record. It enables systematic examination of voter participation, ballot validity, and administrative performance across all sixteen (16) districts of the Banaadir Region, offering insights not only into electoral behavior but also into the operational capacity of local institutions reintroduced after more than half a century of absence.

However, the district-level voting data from Banaadir Region offers an empirical foundation for examining electoral participation, ballot validity, and administrative performance within an urban local-government setting. Across the sixteen (16) districts, a total of approximately two hundred thirty-three thousand three hundred fifty-four (233,354) ballots were cast, reflecting a substantial level of civic participation. Nevertheless, the distribution of this participation is uneven, revealing notable district-level disparities that warrant careful legal and administrative interpretation.

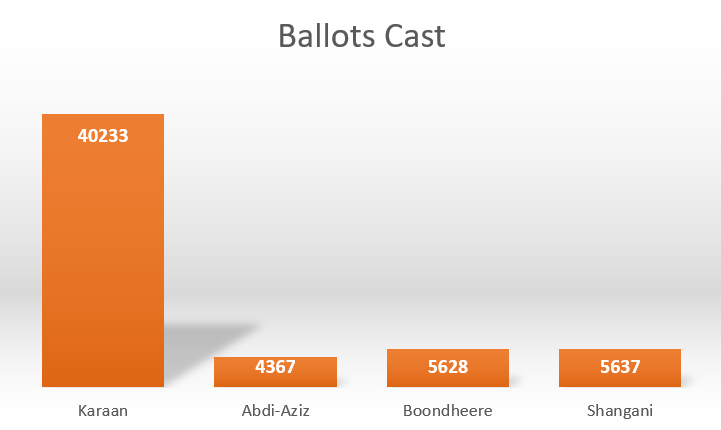

Participation levels vary significantly across districts. Karaan District recorded the highest turnout, with forty thousand two hundred thirty-three (40,233) ballots cast, marking it as the district with the strongest numerical participation. This figure is considerably higher than the regional average and is plausibly explained by Karaan’s population density, expansive residential areas, and the presence of multiple polling stations capable of accommodating large voter flows.

In contrast, AbdiAziiz District recorded the lowest turnout, with only four thousand three hundred sixty-seven (4,367) ballots cast. Similarly, low participation figures were observed in Boondheere with five thousand six hundred twenty-eight (5,628) ballots and Shangani with five thousand six hundred thirty-seven (5,637) ballots. These disparities suggest that turnout correlates closely with demographic size and urban settlement patterns rather than with legal exclusion or procedural barriers.

The figure (1) illustrates a comparative turnout distribution across selected Banaadir districts, highlighting pronounced disparities in electoral participation. As shown in the figure below: –

An examination of ballot validity indicates that the majority of ballots cast across Banaadir were valid. Out of the total ballots, approximately two hundred six thousand eight hundred twenty-one (206,821) were counted as valid, while about twenty thousand eight hundred fifty-six (20,856) were classified as spoiled. This places the overall proportion of spoiled ballots at roughly nine percent (9%), a figure that falls within internationally observed ranges for urban local elections. From a legal standpoint, spoiled ballots are an anticipated outcome of electoral processes and commonly arise from incorrect marking, multiple selections, unclear voter intent, or technical errors during ballot handling.

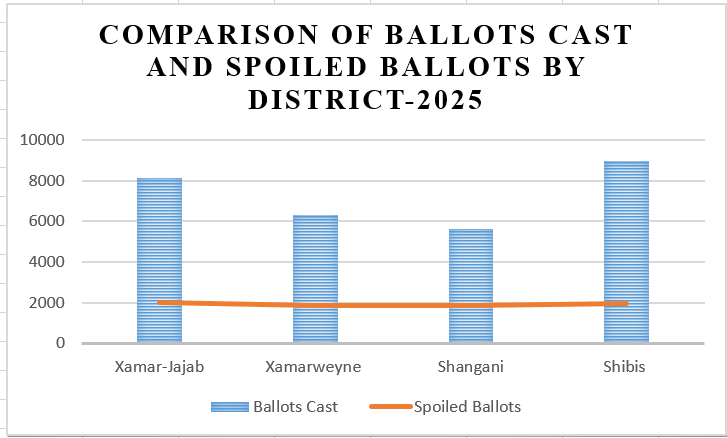

More nuanced insights emerge when spoiled ballots are examined relative to turnout at the district level. Certain districts exhibit comparatively high proportions of spoiled ballots despite recording moderate or low turnout. Xamar-Jajab, for example, recorded eight thousand one hundred thirty-six (8,136) ballots cast, of which two thousand six (2,006) were spoiled. Xamarweyne reported six thousand three hundred (6,300) ballots cast, with one thousand eight hundred eighty-five (1,885) spoiled ballots. Similarly, Shangani recorded five thousand six hundred thirty-seven (5,637) ballots, with one thousand eight hundred seventy-two (1,872) classified as spoiled, while Shibis recorded eight thousand nine hundred seventy-three (8,973) ballots, including one thousand nine hundred twenty-three (1,923) spoiled votes. In these districts, spoiled ballots represent a substantial share of total participation, indicating localized challenges rather than systemic legal deficiencies.

Figure (2): Spoiled Ballots Relative to Turnout in Selected Banaadir Districts as depicted below; –

Conversely, districts such as Dharkenley, Wartanabadda, Heliwaa, and Howl-Wadaag demonstrate a closer alignment between total ballots cast and valid votes. Dharkenley, for instance, recorded twenty-three thousand three hundred eighty-six (23,386) ballots cast, with only four hundred eighty-seven (487) spoiled. Wartanabadda reported sixteen thousand seven hundred fifty-one (16,751) ballots, of which four hundred fifty-two (452) were spoiled, while Heliwaa recorded eight thousand three hundred thirty-five (8,335) ballots with three hundred eight (308) spoiled. These figures suggest relatively effective voter familiarity with ballot procedures and more consistent polling-station management.

From an administrative-law perspective, these variations do not undermine the legality or validity of the electoral process. Rather, they highlight the differentiated impact of uniform electoral rules across diverse urban contexts. Higher proportions of spoiled ballots in certain districts function as empirical indicators of potential gaps in voter education, ballot clarity, or polling-official guidance, particularly in older urban areas characterized by high mobility and mixed residential use.

Category B Districts (21 Seats Each)

| District | Category | Seats | Candidates | Total Votes | Valid Votes | Spoiled Votes |

| Shangani | B | 21 | 79 | 5,637 | 3,765 | 1,872 |

| Xamarweyne | B | 21 | 89 | 6,300 | 4,415 | 1,885 |

| Boondheere | B | 21 | 87 | 5,628 | 5,283 | 345 |

| Shibis | B | 21 | 74 | 8,973 | 7,050 | 1,923 |

| Xamar-Jajab | B | 21 | 95 | 8,136 | 6,130 | 2,006 |

| Waaberi | B | 21 | 100 | 6,188 | 5,969 | 219 |

| Cabdicasiis | B | 21 | 83 | 4,367 | 4,141 | 226 |

Category A Districts (27 Seats Each)

| District | Category | Seats | Candidates | Total Votes | Valid Votes | Spoiled Votes |

| Karaan | A | 27 | 115 | 40,233 | 36,583 | 3,650 |

| Hodan | A | 27 | 127 | 24,956 | 22,690 | 2,266 |

| Yaaqshid | A | 27 | 132 | 24,524 | 21,956 | 2,568 |

| Dayniile | A | 27 | 100 | 19,351 | 17,327 | 2,024 |

| Howl-Wadaag | A | 27 | 105 | 7,910 | 7,693 | 217 |

| Wartanabadda | A | 27 | 99 | 16,751 | 16,299 | 452 |

| Wadajir | A | 27 | 113 | 22,639 | 20,359 | 2,280 |

| Dharkenley | A | 27 | 119 | 23,386 | 22,899 | 487 |

| Heliwaa | A | 27 | 87 | 8,335 | 8,027 | 308 |

In conclusion, the Banaadir district voting data reflects a broadly functional electoral process, marked by strong participation in high-density districts and manageable levels of ballot invalidation overall. Karaan emerges as the district with the highest turnout (40,233), while Cabdicasiis records the lowest (4,367). Districts such as Xamar-Jajab, Xamarweyne, Shangani, and Shibis exhibit comparatively high proportions of spoiled ballots relative to turnout, a pattern that reasonably warrants targeted administrative and civic-education review. A legally sound response lies not in questioning electoral legitimacy, but in refining voter education, improving ballot design, and strengthening polling procedures to ensure the effective realization of the right to vote across all sixteen (16) districts.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Targeted Voter Education: Electoral authorities should prioritize district-specific voter education initiatives in areas with consistently high proportions of spoiled ballots. Tailored civic-education campaigns, particularly in older and mixed-use urban districts, can address common ballot-marking errors and improve voter confidence.

- Ballot Design Review: A technical review of ballot layout and instructions should be undertaken to ensure clarity, simplicity, and accessibility. Minor design adjustments may significantly reduce inadvertent invalidation without altering substantive electoral rules.

- Polling-Station Capacity Building: Enhanced training for polling officials especially in districts with high invalidation rates should focus on standardized voter guidance, queue management, and error prevention while maintaining strict neutrality.

- Data-Driven Administrative Monitoring: Electoral management bodies should institutionalize post-election district-level data analysis as a routine administrative practice. Such monitoring allows early identification of recurring patterns and supports evidence-based policy responses.

- Differentiated Administrative Support: While electoral rules must remain uniform, administrative support need not be identical across districts. Allocating additional resources to districts exhibiting higher administrative strain can improve procedural outcomes without compromising legal equality.

No comment